An analysis of the systemic problem of the lack of individual notification to property owners about changes in Local Spatial Development Plans (MPZP). How information asymmetry favors the 'insiders' and undermines the constitutional rights of citizens, creating inequality and generating local social disputes and unrest.

Table of Contents

Today I am continuing the topic started in the last post about urban activism and urban chaos, but from a different angle. Observing the protests and problems surrounding the issue of land and property owners, I see a certain pattern. Protests erupt not only because of issued zoning decisions (WZ), but now primarily as a result of the processing of Local Spatial Development Plans (MPZP).

Imagine you are the owner of a plot of land in a picturesque area, perhaps even hundreds of kilometers from where you live. You have plans, dreams related to this property. And then suddenly, often by chance, you find out that your plans have been shattered. Why? Because the municipality “quietly” implemented or changed the Local Spatial Development Plan (MPZP), and you, as the owner, were not individually informed about it. Suddenly, it may turn out that the quiet neighborhood is a thing of the past and they can build a chicken coop, a waste sorting plant or a DIY store, and you won’t be able to build anything because a meadow is planned there to protect biodiversity, which was not considered when the whole area was concreted over. Does it sound like a nightmare scenario? Unfortunately, this is the Polish reality, resulting from a systemic problem that can be described as information asymmetry. Today I will show you how some are better informed than others and what this leads to.

The problem hidden in the law

During one of the meetings in Wrocław, I witnessed a situation where the owner of a large plot of land near Łódź learned from me - a third party - that the processed MPZP would probably prevent him from any development. And this person will probably not be able to do anything about it. How is this possible in a country of law?

Current regulations (mainly Art. 17 of the Act on Spatial Planning and Development) impose on municipalities the obligation to inform about the commencement of the preparation of an MPZP through:

- Announcement in the local press

- Notice on the notice board in the municipal/city hall

- Publication in the Public Information Bulletin (BIP)

At no stage is there a requirement for individual, written notification of the property owners who are directly affected by these changes. This means that although the constitution protects private property, it does so in a strange way, since as an owner I am not informed about key procedures for my property. In practice, this means that if you do not live permanently in a given locality, do not subscribe to the local press (whose reach varies), or do not regularly follow the BIP of a given municipality, you have little chance of finding out about the procedure in time to submit applications or comments. You will not receive a registered letter, no one will call you with information that something bad is happening. What’s more, municipalities often inform about the MPZP through Facebook profiles, treating this closed distribution channel as a good tool for informing residents.

Information asymmetry in practice

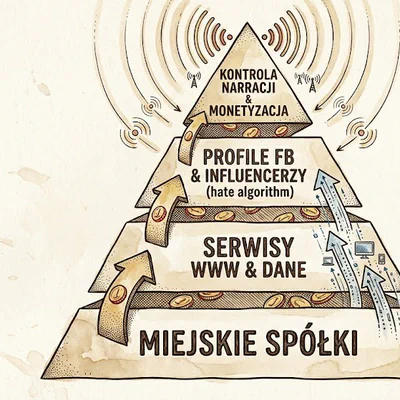

This state of affairs creates a classic information asymmetry. On the one hand, we have officials, planners, local developers, or simply “well-informed” people who have access to knowledge about planned changes at an early stage. They can actively participate in the process, submit applications consistent with their interests, and even (in extreme cases) use this knowledge for speculative purposes. Let’s not kid ourselves, this is probably common…

On the other hand, there is the average property owner, especially one living elsewhere (e.g., in Łódź, owning a plot in Wrocław). For him, tracking dozens or hundreds of municipal BIPs throughout Poland is physically impossible. He finds out about the matter when the “train has already left the station” - the deadlines for submitting applications and comments have long passed. Besides, these comments to the MPZP are often a fiction, because strangely enough, most of the comments from residents and owners of small plots are rejected, but those comments that allow for squeezing out the PUM (usable residential area, which determines the developer’s profit) are beneficial for a few people who have owned plots in the area for several years. Well, they must have taken a risk or played a blind game, since they “pickled” their assets for so long for arrangements favorable to themselves. I have heard of cases where people introduced to the Neighborhood Council specially pushed for certain options among the local community that were attractive to the developer. The insert included an addition in the form of an extra that was attractive to the residents.

This situation favors the “insiders”. It is precisely those who “guard their topics”, often having informal contacts in offices, who are the beneficiaries of the current system. The rest, i.e., the majority of owners, remain in an information vacuum. Bartosz Józefiak wrote about this in his book Patodeweloperka (Patho-development).

Constitutional doubts remain unanswered

However, I wonder whether such a selective mode of information is constitutional. After all, it raises fundamental questions about the compliance of such a system with the Polish Constitution:

Protection of the right to property (Articles 21 and 64): Does restricting the use of real estate, without effectively informing the owner about the process leading to these restrictions, not violate the essence of this right?

The right to public information (Article 61): Do the current, ineffective methods of information implement the citizen’s constitutional right to knowledge about the actions of public authorities that directly affect their legal situation?

The principle of proportionality (Article 31): Are the current, minimal information standards adequate for the purpose of efficient planning, and at the same time, do they not excessively restrict citizens’ rights?

Interestingly, as indicated by legal expert Szymon Dubiel from Watchdog Polska, to whom I wrote about this matter, “so far there have been no rulings of the Constitutional Tribunal regarding the compliance of the current regulations related to the system of informing about changes in spatial development with the Constitution.”

This means that despite the doubts raised, the key issue of the constitutionality of the information system itself has not yet been unequivocally resolved at the highest judicial level. Previous rulings (e.g., Kp 7/09 from 2011) recognized the formal methods as sufficient, but did not necessarily refer directly to the effectiveness and the problem of non-resident owners in today’s context. Administrative courts sometimes repeal plans due to insufficient information, but there is no systemic solution.

Social consequences of under-information

In my opinion, the current system generates numerous problems, and I suspect that this is not accidental:

Late protests: Owners, learning about unfavorable changes “after the fact”, often try to “sabotage” the process at later stages, which leads to conflicts and delays. We observe this in our own and neighboring housing estates.

A sense of injustice: Citizens feel left out of the decision-making process concerning their own property.

Inefficient planning: Conflicts and lack of social acceptance make it difficult to rationally shape space. The Municipal Urban Planning Studio with its architects work under pressure from developers/owners of large investment plots and the local community.

Undermining trust: This practice undermines trust in local governments and public institutions. Yes, we will repeat this again, it undermines trust in public institutions.

Is it time for a systemic reform?

I am not a lawyer, but I believe that in the era of digitization, ePUAP, and central real estate registers (like the Land and Building Register), maintaining an information system from a previous era seems anachronistic. Possible solutions include:

Introduction of a statutory obligation of individual notification of owners (by letter or electronically, e.g., via ePUAP) about the initiation of an MPZP procedure concerning their property, or changes under the Lex Developer.

Creation of a central, nationwide portal informing about all planning procedures in the country - this condition will probably be met by the created Urban Register, which will start operating on January 1, 2026.

Extension of deadlines for submitting applications and comments - however, this seems impossible given the requirement to introduce plans and the terrible neglect and delays in this area.

Mandatory, widely promoted information meetings for residents and owners. Although, to be honest, these meetings with the deputy of Zdanowska in the person of Mr. Pustelnik, who with buttery eyes talks about private property, and whose Facebook profile is full of posts about new developer investments or meetings with developers… I have limited trust in such initiatives of eyewashing and playing for time.

Arguments about increased costs or lengthening the procedure are often raised, but can the convenience of the administration be placed above the fundamental right of a citizen to information and the protection of their property?

Is it already too late for changes?

I have been observing the problems here for several years. I have worked with two law firms on investment matters and I see a very big problem at the local community level in information asymmetry in spatial planning. And no, this is not just a technical inconvenience. It is a systemic flaw that gives rise to real conflicts, a sense of injustice, and undermines trust in the state. It is also an area for possible speculation and manipulation of the decision-making process. It is time for a serious debate and legislative changes that will ensure that every property owner in Poland has a real, not just illusory, opportunity to participate in the process that decides the future of their property.

Is the current system just an oversight, or perhaps a convenient “gray area”? Regardless of the answer, it requires urgent repair. It’s a shame that people dealing with patho-development and urban processes do not address this issue.

The article was written on the basis of an analysis of the applicable regulations on spatial planning and observation of the practice of their application. The author thanks the people who consulted on the substantive issues for answering the questions. I am open to correcting the article if it has substantive flaws.