How urban chaos and passive investments turned the resort town of Szklarska Poręba into the most literal example of infrastructure collapse. An analysis of mechanisms that allow developers to pump profits while residents get sewage in the river and bills for someone else's business.

Table of Contents

During a mountain getaway, we drive into Szklarska Poręba. This town, known for high tourist occupancy, is attractive due to its unique status as a climatic resort, with conditions comparable to Alpine villages. Its location among peat bogs, proximity to the Karkonosze Mountains, and specific microclimate create an ideal place for athletes and spa visitors. At least that’s what the promotional materials say. This town, which symbolically held dominion over the Spirit of the Mountains, today struggles to control its own very earthly spirit – the logic of short-term profit.

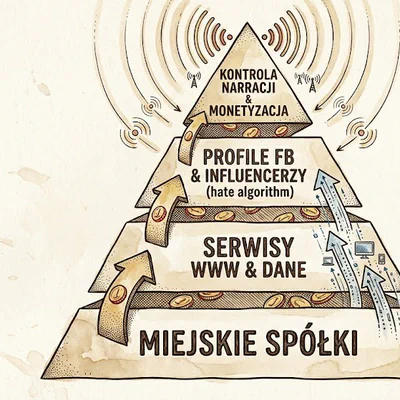

Driving through Szklarska Poręba, it’s hard to resist the impression of excess and architectural chaos. There are countless hotels, guesthouses, and investment apartments here, built almost exclusively for parking capital – a manifestation of the “Investment Mountains” phenomenon. It’s capital that promises passive income but generates very active social and environmental costs.

Capitalism Spills Sewage: A Metric of Chaos

The all-encompassing urban chaos and overtourism are, however, just the tip of the iceberg. Unfortunately, from the very entrance, along the Kamienna River, we’re hit by the ubiquitous smell of feces. This horrific stench is the most literal and tangible effect of urban chaos. To put it bluntly: in Szklarska Poręba, infrastructure cannot keep up with greed.

The problem of sewage discharge into the river, revealed for years, is the result of infrastructure collapse. It’s the logical consequence of planning decisions that, in the name of quick tax revenues and connection fees, allowed for multiple exceedances of the real capacity of the municipal network.

Crucially, the local sewage treatment plant is permanently inadequate. Its actual capacity is 2,000 cubic meters per day, while standard inflow is 2,500–3,000 cubic meters, and during peak tourist moments, 7,000 cubic meters were recorded. This glaring disproportion means the plant was inadequate already at the time of acceptance or shortly after due to uncontrolled development growth (behemoths with 3,000 beds, like the Radisson or Platinum hotels, are just examples). This resulted in sewage being legally discharged into the river (under permits). As a result, the Kamienna River has become a brown sewer, and wherever it flows, the odor of feces spreads for several hundred meters.

Most outrageously, the company responsible for sewage continues to approve connections for additional buildings – which is de facto legal consent for further environmental devastation and pumping more cubic meters of feces into the river. The stench is therefore a negative externality of privileging capital over basic sanitary needs (meaning the costs of profits are borne not by the investor, but by the environment and local community).

The Logic of Urban Chaos and Planning Error

The chaos in Szklarska Poręba isn’t just visual clutter; it’s primarily a lack of coordination between construction development and the town’s technical capabilities. Local authorities, even while admitting they lack tools to control development, seem to succumb to profit maximization logic.

As a result, the town faces:

- Destruction of social fabric: Rapid property price increases, driven by investment demand (apartments are expensive), lead to displacement of permanent residents to cheaper Jelenia Góra. As residents indicate, profits from large, newly opened hotels often go to foreign companies, and they mainly employ workers from outside the town, meaning the local community doesn’t benefit proportionally to the infrastructure burden.

- Planning kitsch: Szklarska Poręba historically imposed “pseudo-manor architecture” patterns on investors – showing that the problem lay not only in lack of plans, but in imposing bad and aesthetically poor guidelines, leading to visual kitsch and lack of coherence.

Residents as Decoration for Passive Investments

In the era of “Investment Mountains,” the permanent resident of Szklarska Poręba becomes merely a decorative element in a developer’s catalog.

Tourism based on passive investments requires the resort to look charming. Real residents, who create the local economy and services, become unwitting extras in a luxury tourist spectacle.

However, when infrastructure capitulates (water shortages, sewage stench, traffic jams, high prices), their status changes from decoration to victims of the system. Worse still, they will be forced to cover the costs of infrastructure debt generated by investors. The planned modernization of the treatment plant (cost approx. 20 million PLN) is to be secured by municipal assets and financed by fee increases for residents (up to 5 PLN/m³), making water and sewage among the most expensive in Poland. Residents must therefore subsidize investors’ business.

This is a warning for all municipalities that treat real estate developers as a free ATM and spatial planning as a necessary evil. Without responsible urban planning and infrastructure priority, even the most beautiful mountains will turn into the most expensive sewage pit in Poland, whose costs everyone will bear, regardless of their wallet. Chaos already affects every region of Poland, from the sea to the mountains, residents and tourists waste hours in traffic on congested roads, ultimately forcing them to flee to increasingly distant, still-undestroyed places.

Postulate: End the Illusion of Free Infrastructure.

To avoid this scenario nationwide, a fundamental change is necessary: no new building permit can be issued until the local government presents a public technical and financial audit, confirming not only the real reserve of infrastructure capacity (water, sewage), but also a guarantee of its financing without burdening permanent residents.