Analysis of mechanisms for promoting conspiracy theories in civic media, using Rafał Górski's columns about the Smolensk crash and JFK assassination as an example.

Table of Contents

I stumbled upon the Civic Affairs Institute (ISO) as an interesting object of analysis by chance. During urban activities, I received information from serious people about activists engaging in blocking various initiatives in Łódź, from waste incinerators to 5G masts, in a style bordering on paranoid narratives and conspiracy theories. Sensitive to such narratives, I decided to take a closer look at ISO, which I had previously known only superficially from press publications.

I delved into their financial documentation and articles published under so-called citizen journalism. It quickly became apparent that this was an extremely interesting research direction, especially in the context of Łódź – a city proud of its high concentration of activism, though of quite questionable effectiveness.

I will analyze ISO more deeply because their campaigns such as “Defend Cash” (repeatedly debunked by Demagog.org.pl) or waste sorting issues constitute a fascinating case study. Today, however, on the 15th anniversary of the Smolensk crash, I would like to analyze the articles by ISO’s director, Rafał Górski.

Although the opinion section on the ISO website functions as part of so-called citizen journalism (one could ask whether this is just a decoration for grant applications, but that’s a topic beyond the scope of this blog), in my opinion, the views presented by Górski, as well as his image, are inextricably linked to the entire organization. Hence, I analyze these articles as part of a broader phenomenon.

On this anniversary, it’s worth examining how conspiracy narratives surrounding the Smolensk crash have become a permanent element of Polish public discourse. This is not a marginal phenomenon - conspiracy theories penetrate mainstream media, and even more frequently appear in alternative and civic media spaces, which are supposed to be a counterweight to official narratives.

Today, we’ll begin by analyzing two columns by Rafał Górski, published in the Civic Affairs Weekly (issued by the Civic Affairs Institute). These texts are particularly interesting because they represent an example of how seemingly objective analysis can be a tool for promoting conspiracy narratives under the guise of citizen journalism and critical thinking. Discussing these techniques does not mean accepting or legitimizing the claims contained within them.

Conspiracy Narrative Structure - Recurring Scheme

The columns by Górski that I analyzed – “Kaczyński, Roldós, Torrijos – Plane Accidents or Political Assassinations?” (April 2022) and “Who Killed Kennedy? The Practice of Conspiracy” (November 2022) – show striking structural similarities characteristic of conspiracy theory promotion.

It’s worth emphasizing that the analysis presented below is not meant to reproduce or reinforce conspiracy theories, but to deconstruct the techniques used to propagate them. For me, it’s an interesting exercise to explore such trails, but I hope that understanding these mechanisms can help Esteemed Readers critically evaluate similar content they may encounter in the public space. If I’m honest, the world is full of such persuasive strategies. It’s therefore worth knowing them.

1. Lists of “Coincidences”

In both texts, the author uses a similar technique – creating numbered lists of alleged “coincidences” that suggest official explanations are incomplete or false:

- In the article about the Smolensk crash, the author lists ten such “coincidences”, including manipulations with black boxes, destruction of airplane fragments, mysterious deaths of witnesses

- In the text about the JFK assassination, the list contains seven points, including the “magic bullet”, route change, mysterious deaths of witnesses

This rhetorical device creates an impression of a pattern and intentional action where in reality, there may be unrelated facts, inconsistencies, or simple human errors. The conspiracy theorist does not admit to randomness or world chaos. For them, the world is characterized by purposefulness and is ordered. Of course, one only needs to take the red pill and connect the dots appropriately. People naturally seek patterns and connections, even when they don’t exist. The brain cannot tolerate randomness, so it creates patterns for itself. Lists of apparent anomalies are an effective tool because they create the illusion of a coherent explanation. Critical thinking allows me to subject such paranoid dot-connecting to falsification and confirm (then the conspiracy theory becomes a fact) or refute it. If something is unfalsifiable, it meets 100% of the conditions of a classic conspiracy theory.

2. Connecting Unrelated Events

Equally characteristic is the search for analogies between unrelated historical events. Górski compares the Smolensk crash with the deaths of presidents of Ecuador and Panama in the 1980s, suggesting a common denominator:

“What connects the deaths of these three presidents?”

In the JFK article, the author also seeks analogies with the Smolensk crash:

“When I read about all this, I was reminded of the list of coincidences related to the Smolensk crash…”

What’s the point of this technique? Such comparisons create the impression of a global pattern and a timeless mechanism in which mysterious forces eliminate inconvenient politicians. This is a classic element of conspiracy narratives. Suggesting a grand, timeless conspiracy without presenting evidence of actual connections between events. Just seeing this, the conspiracy theorist guides the message recipient by asking only questions.

3. Selective Citation of Authorities

In both articles, Górski selectively refers to authorities that support his narrative while ignoring the main body of research and expertise:

- In the text about JFK, he invokes prosecutor Jim Garrison and his investigation, which historians criticize for serious methodological errors

- In the Smolensk article, he quotes former US Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller, who allegedly called the crash a “brutal murder committed by Putin”

It’s hard for people to accept that the president and top officials likely died due to negligence and violation of elementary safety rules. Górski leaves no room for final reports and does not deconstruct the theses contained therein. This selectivity is a fundamental element of building a conspiracy narrative. Only sources supporting the conspiracy thesis are chosen, while simultaneously ignoring or discrediting sources presenting more complex, nuanced explanations.

4. Rhetorical Questions Technique (JAQing off)

A characteristic element of both columns is the abundant use of rhetorical questions that suggest a conspiracy without the need to present evidence:

“Did the presidents of Poland, Ecuador, and Panama die in plane accidents or political assassinations?”

“Who benefited from killing JFK?”

This technique allows Górski to formally avoid making an unequivocal statement that the event was the result of a conspiracy while simultaneously directing the reader towards such a conclusion. This is a classic example of the so-called JAQing off (Just Asking Questions) disinformation technique widely used by conspiracy theorists. Recently, the most popular podcaster Joe Rogan has been a master of this technique.

The term “JAQing off” is a wordplay referring to the English term for masturbation (“jacking off”). It means to brandle, which emphasizes the self-satisfying nature of this practice. It provides pleasure mainly to the person asking questions and does not serve to actually acquire knowledge. This technique allows shifting the burden of proof to the opponent and avoiding responsibility for making controversial claims. In the event of criticism, the author can always defend themselves by saying: “I was just asking questions!”. An excellent technique – internalize it, because it is widely used by politicians.

In Górski’s columns, this tactic is clearly visible. The questions are not posed to reach the truth but serve to undermine official explanations and suggest alternative, conspiracy-driven narratives without having to prove them.

Mechanisms of Conspiracy Narrative Legitimization

Górski uses several techniques to make the promoted conspiracy theories credible to readers. Identifying and analyzing these techniques does not mean they have actual evidentiary value. In my opinion, quite the contrary – the value of my approach allows maintaining a critical distance from the content promoted by the author.

1. Appearance of Objectivity and Symmetry

The author presents himself as an objective analyst who merely considers various possibilities:

“I would wish for members and experts of the Macierewicz Commission and the Miller Commission to meet and exchange arguments.”

This apparent impartiality serves as a protective layer for the promoted conspiracy narrative. In reality, both texts are constructed to lead the reader to a specific conclusion. Which one? Of course, that official explanations are false, and the truth about the conspiracy is being hidden.

2. Appealing to “Common Sense”

Górski often contrasts official explanations with “common sense”:

“Really, one needs a lot of sick sense to believe that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.”

This technique aims to discredit complex scientific and investigative explanations as detached from reality while presenting simple, conspiracy-driven narratives as “obvious”. Common sense is the basis of every conspiracy theory. It is the individual, not authorities or mainstream media, who has the competence to judge what is true and what is not. Just do your own research.

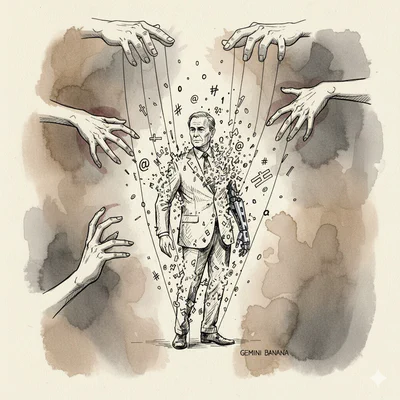

3. Building a Narrative of Victims and Heroes

In Górski’s texts, there is a clear construction of a narrative with:

- Victims (Kennedy, Kaczyński) – noble leaders eliminated by mysterious forces

- Heroes (Garrison, Macierewicz) – brave truth-seekers fighting the system

- Villains (CIA, Russians, mysterious deep state) – powerful forces acting in secret

This simple narrative scheme is attractive because it simplifies complex reality into a form close to fairy tales or myths, with a clear division between good and evil. This binary way of thinking is prototypical for conspiracy theorists. In the world of paranoids, there is no room for coincidence, only conspiracies.

Social Consequences of Promoting Conspiracy Theories

Górski’s columns are an example of a broader phenomenon – the normalization of conspiracy narratives in the public space. These are not marginal publications - they appear in a periodical published by the Civic Affairs Institute, an organization with significant public funds, whose revenues in 2022 exceeded 6 million zlotys, including over 100,000 zlotys from the National Institute of Freedom. ISO implements several social projects, from supporting social economy to campaigns about GMO and rail transport. This shows how conspiracy theories penetrate the mainstream discourse, especially in civic and alternative media spaces.

The consequences of this phenomenon are serious:

- Erosion of trust in public institutions – systematically undermining official explanations and expert opinions leads to a decline in trust in the state and its institutions

- Social polarization – conspiracy narratives often divide society into “those who know the truth” and the “blinded crowd”

- Difficulty in conducting substantive debate – when part of the discourse participants operate in an alternative fact system, a substantive debate becomes impossible, because it’s hard to discuss with paranoids who have their own version of truth invisible to others.

A Mousetrap? Civic Media: Responsibility and Pitfalls

Particularly disturbing is the fact that the analyzed texts appear in media that are supposed to be the voice of civil society. The Civic Affairs Institute presents itself as an organization working for a conscious society, and their weekly carries the subtitle “Column Supported by Facts”.

This facade of objectivity and acting in the public interest makes conspiracy theories presented in these media potentially more credible. After all, they are not presented by a tabloid or an extreme portal, but by an institution with a civic mission. Interestingly, many activists or institutions I spoke with distance themselves from ISO publications, and some urban activists familiar with ISO initiatives were unaware of the controversial publications.

It’s worth noting that Górski ends the Smolensk article with a personal reference:

“Twenty-seven years of actions on citizen campaign fronts taught me to believe in people like Garrison, Robert Bilott, Edward Snowden, Jolanta Brzeska, or Przemysław Pasek, and to approach explanations from powerful interest groups with distance.”

This is a typical technique of building authority by identifying with actual whistleblowers like Snowden. The problem is that juxtaposing reliable whistleblowers with conspiracy theory promoters serves to legitimize the latter and blur the boundary between revealing actual abuses and promoting unconfirmed theories.

Conclusions

I’m starting a whole series about ISO. The columns by Rafał Górski analyzed today are an example of a phenomenon that can be called “civic promotion of conspiracy theories” – using the structures and language of citizen journalism to spread conspiracy narratives.

In this case, we are dealing with texts that:

- Seemingly maintain objectivity by asking questions instead of making statements

- Use precisely constructed rhetorical techniques typical of conspiracy theory promotion

- Legitimize alternative narratives by selectively citing authorities

- Build bridges between different conspiracy theories, creating the impression of a coherent system

I want to emphasize that the purpose of this analysis is not to assess the actual truth of the claims in Górski’s texts, but to deconstruct the rhetoric and narrative techniques he uses. The mere identification of conspiracy theory promotion mechanisms does not constitute either confirmation or denial of official findings regarding the discussed events. Studying such mechanisms is essential for developing critical information consumption skills and should not be confused with legitimizing the analyzed content.

On the anniversary of the Smolensk crash, it’s worth remembering that critical thinking does not mean automatically rejecting official explanations, but involves rigorous analysis of available evidence, awareness of one’s own cognitive biases, and readiness to accept complex, ambiguous explanations.

Genuine citizen journalism should ask difficult questions and control power, but at the same time rely on facts and evidence, not on insinuations and rhetorical tricks. Only then can it effectively serve as a guardian of democracy.

Sources

Górski, R. (2022). Who Killed Kennedy? The Practice of Conspiracy. Civic Affairs Weekly, No. 150.

Wikipedia “Just Asking Questions” (JAQ; known derisively as “JAQing off”)