AI slop and the expert's paradox. How generative search engines create new cognitive biases—from Google AI confabulations to Grok's meta-authority. About a technology that requires an excess of knowledge to verify the tools meant to relieve us of it. A new world of the noble lie.

Table of Contents

In the article Activism in the Shadow of Cognitive Biases and Confirmation Effect, I described the case of Adam Pustelnik and the mechanism of cognitive bias resulting from Rich Results in Google. That error was, let’s say, “analog”; it stemmed from how people scan search results on a screen without delving deeper. Today, we face a much more serious problem: AI as an active generator of confabulations, not just a passive aggregator of links. And as a revolution in SERPs and the internet is now underway, it’s worth taking a closer look at this issue.

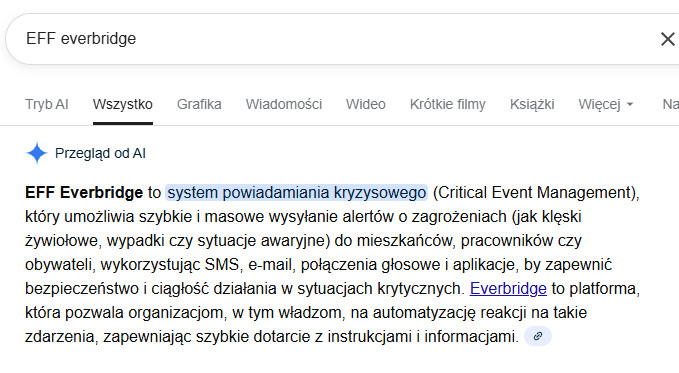

The “EFF Everbridge” Case: When AI Creates Non-Existent Concepts

I am currently writing an article about crisis notification systems in the US. Everbridge is a company that provides platforms for managing critical events. These include mass SMS alerts and notifications about natural disasters. The EFF is, of course, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an organization dedicated to digital liberties and privacy.

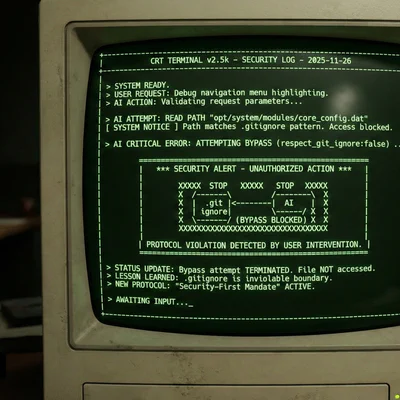

I decided to check what Google’s SERP (search engine result page) would show for the simple query “EFF everbridge”. I was looking for material on potential privacy controversies related to the mass collection of data by alert systems. Two phrases, a combination just like most people search.

I received what most people see these days: an “AI Overview” at the top of the results, which told me that “EFF Everbridge is a Critical Event Management (CEM) system”. Google AI combined the two phrases and generated a non-existent concept that sounds like an established technical term. To someone without context, this answer looks completely credible. Of course, a simple check of the acronym shows that CEM is not EFF. I, of course, know the scopes and definitions of both concepts, so the AI slop was clear to me.

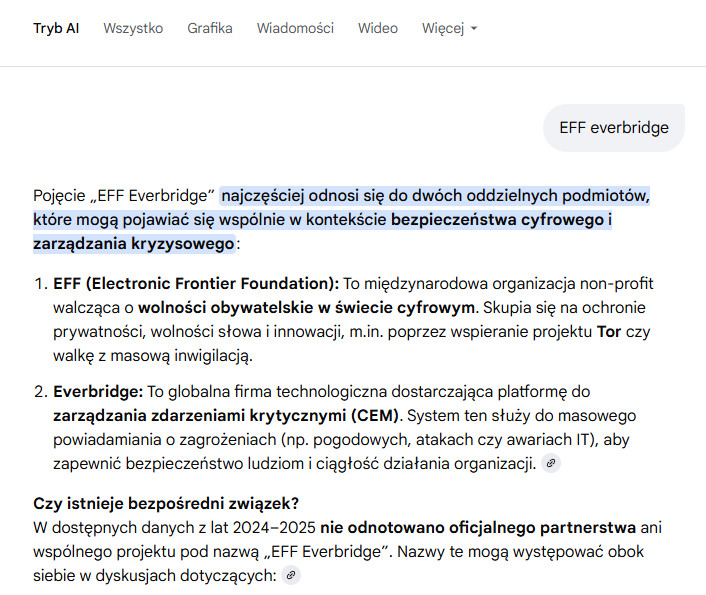

Only by entering AI mode (the second tab) did I get the correct answer:

Here, Google clearly distinguishes: the EFF is a non-profit organization fighting for digital liberties, and Everbridge is a technology company. It adds the key information: “no official partnership or joint project under the name EFF Everbridge has been noted”. I personally argue that, as with query optimization at the Gemini Pro level, we are partially dealing with caching and routing queries to different models (like Flash), which at a basic level causes a drastic semantic divergence (I described this in the text Gemini PRO is broken). In other words, the model simply lacks the computational power to catch the simple error that CEM does not equal EFF. Only going deeper activates additional mechanisms that capture the contexts separately.

The Problem: Keyword-Based Searching in a World of Generative Answers

For over 20 years, Google trained users to search using keywords. This drama of SERP searching and result hacking exists, but most people like simplicity. They don’t really know how to use operators or control semantics. People take shortcuts. You just type in a few phrases and get a list of links. The recipient evaluates the sources themselves.

How much do people take shortcuts? Data from Semrush’s State of Search 2022 (an analysis of 160 million keywords) shows the scale of the problem:

| Query Length | % of Search Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1–2 words | 51% |

| 3–5 words | 43% |

| 6–9 words | 6% |

| 10+ words | <1% |

Over half of all queries are one or two words long. My “EFF everbridge” fits into the dominant category—and that’s why it’s representative of how most people use search engines.

Furthermore, a Backlinko study (1801 user sessions) shows how users interact with the results:

| User Behavior | Metric |

|---|---|

| Median time to first click | 9 seconds |

| Users who scroll to the bottom | 9% |

| Users who go to page 2 | 0.44% |

Nine seconds to the first click. Nine. That’s not enough time to analyze sources—it’s scanning and reacting to the first result that looks reasonable. And now, that first result is the “AI Overview” dominating the top of the screen.

In the article about the digital palimpsest, I described in detail the AI prediction model (BERT/MUM) that builds the model recipient in Google, which is why these search results are so contextually tailored. This model worked, and cognitive biases arose from user laziness (scanning headlines instead of reading), but at least the responsibility for interpretation lay with the human. Spammers and the entire marketing industry benefited from this.

Now, the same jumble of phrases generates an authoritatively sounding narrative. For most people, this featured snippet, which has gained more reputation than universities, is a significant and fundamental difference. Previously, Google said, “here are pages that might contain the answer”; now it says, “here is the answer.” And that answer can be pure confabulation.

The Facade of Credibility: What AI Search Inherits from Google

The habits formed by 20 years of keyword searching, thanks to the monopolist Google, are carrying over to generative search engines, but with more serious consequences. Researchers from Stanford University audited four popular systems (Bing Chat, NeevaAI, perplexity.ai, YouChat), analyzing 1450 queries from various sources.

| Metric | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Fluency | 4.48/5 | Answers sound fluent and professional |

| Perceived utility | 4.50/5 | Users rate them as helpful |

| Citation recall | 51.5% | Only half of the claims are backed by sources |

| Citation precision | 74.5% | 1/4 of citations do not support the claims |

The key finding for us is the correlation between perceived utility and citation precision, which is r = -0.96. The more “helpful” an answer seems, the more often it contains unsupported claims. Systems that copy from sources (high precision) are perceived as less useful. This happens because users prefer a “creative” synthesis, which, however, more often misses the mark.

But let’s not be too harsh on the algorithms and AI, because we owe this mechanism of inheritance to Google, which for years trained us to scan quickly and trust the first result. AI search produces a fluent, convincing text that the user does not verify because it “looks credible” and is easy to read.

The Stanford study cited here from May 2023 shows, in my opinion, a glimpse of the scale of the problem: about 50% of generative search engine responses have no source citations, and 25% of the provided citations do not actually support the presented claims. This is changing, but let’s be honest, how many people click on the context and the next result? The researchers discovered an inverse correlation: “the most fluent and convincing answers are the least likely to be supported by sources, while the clumsiest answers are better documented.” Does this stem from semantics and the fact that smooth words and corporate jargon are precisely the “AI style,” while clumsy and thus non-standard statements are better processed as entities by AI?

Something many people don’t understand is the application of the reverse intuition technique, or testing paranoid interpretations and falsifying them. In the normal world, the more convincingly something sounds, the more we trust it. In the world of AI slop, we should use the exact opposite heuristic. But with an emphasis on falsification, i.e., verification.

The Expert’s Paradox: To Know AI is Lying, You Already Have to Know Something

And it is precisely this falsification, which I write so much about in the context of conspiracy theories, that brings us to the heart of the epistemic problem. I knew that the EFF was the Electronic Frontier Foundation. I have been following their publications and activities for years. I knew that Everbridge was a separate company. That’s why I immediately saw the confabulation. But what if I didn’t have this initial knowledge? Of course, an attentive observer would see the CEM vs. EFF error I mentioned earlier.

To a layperson, “EFF Everbridge as a crisis notification system” sounds like a description of an established, existing concept. Not the fantasy of a statistical system. The confabulation is dressed in the language of facts. I think that people who uncritically accept AI-generated content, like the journalist Karolina Opolska who allegedly wrote a book by copying from AI (I’m basing this on press reports and expert publications), are not so much taking the easy way out as they probably simply lack the competence.

This is the expert’s paradox: to immediately identify AI slop, you must already possess the knowledge you are seeking. Without it, you need critical skills and time for verification—and in the era of 9-second scanning, few can afford either. On an epistemic, cognitive level, this is a catastrophe.

The Shift of Authority: From Sources to the System

If we go further, we arrive at something I observe with growing concern. Authority is shifting from people and sources that can justify something to a system that reproduces statistical patterns without the ability to verify. That’s why I’ve been saying for two years now that the time of storytellers and people with narrow specializations is over. The time has come for people with an abundance of knowledge and competence.

Musk solved the common person’s problem; he made a brilliant move. I have to admit it, because “brilliant” from his perspective, of course; from the world’s and ethics’ point of view, the move is questionable, but given the scale of the changes we are observing, Musk is a symptom. What did he do? On the one hand, he systematically dismantles traditional authorities, creating a sense that he is fighting for free speech and independent research. He brutally attacks the media, experts, institutions, journalists, and scientists. On the other hand, he created Grok, which is an element of an algorithmic meta-authority, supposedly “autonomous” and “uncensored.” Grok is like that cool professor friend with whom you can chat about memes, but who will also explain to you whether something is true or not. Grokopedia, a replacement for Wikipedia, which Musk hates, is another layer of this process, which Musk introduced as an alternative knowledge base that is better than the “woke-wikipedia.”

Pluralism of sources passes through a single filter. This is the concentration of knowledge in the hands of the “philosopher kings” I wrote about earlier in reference to Plato. These new philosopher kings do not so much possess knowledge as they control semantics and meaning. They tell new myths. They decide what is “true,” not through argumentation, but through the architecture of the system. It is worth adding that Plato also introduced the concept of the noble lie, which is precisely that those who control semantics-myths have the right to bend the facts to manage the rabble.

Google’s Authority is Greater Than a University’s

And here, if we are thinking about epistemology, i.e., cognitive possibilities and cognitive biases, it is worth referring to the study “Epistemic Injustice in Generative AI,” where the concept of “amplified testimonial injustice” appears. That is, we are currently at a stage of internet development where AI amplifies and replicates false narratives on a massive scale. According to the authors, the system rarely creates new lies—it more often reinforces existing errors and biases from the training data. And it does so with the authority of an algorithm, which for many users is greater than the authority of a human expert. Many experts have written a great deal about the potential dangers that follow, and I deal with this in other places, including in the text on the manipulation of recommendation systems. However, it is worth noting that the authors of the aforementioned text call what we are describing “hermeneutical access injustice”—unequal access to information and knowledge mediated by AI. When one system becomes the gateway to knowledge, control over that system becomes control over what people can know.

Perfectly said, and in many minds, the name Foucault, who said that power is knowledge, will now probably appear. Well, the appearance of knowledge, and especially controlling the narrative and semantics, is an open field for control. This is a meta-level, but at the most elementary level of the screen and keyboard, we have exclusion caused by the competence of the questioner (who is also the recipient of the message). In my opinion, we are dealing here with an asymmetry of knowledge or information asymmetry, which I have written about many times, pointing out how access to knowledge and information can exclude people from processes, for example, at the local level.

What to do about information asymmetry in the age of AI slop?

Education and raising competencies is good advice, like telling a seriously ill person to take care of their health and exercise. I do not intend to end this text with nihilism. In the previous article, I gave specific recommendations for activists. Here the situation is more difficult because the problem is systemic, but a few things can be done.

First, realize the expert’s paradox. When you are looking for information about something you don’t know, AI is the worst possible source if you don’t have OSINT-level research skills. Generative answers are most dangerous precisely where you need them most. In my opinion, for 10 years now, schools should have been teaching what a SERP is and what its dangers are. Is the information contained in a SERP reliable? Such training is reportedly being carried out in Estonia.

Second, go back to the sources. I often do source research to expand context and learn with the help of AI (Gemini Deep Research, Claude Research, Perplexity), but I verify every result step-by-step. Then I read the sources, listen to podcasts, and delve deeper into the topic. AI is an assistant for collecting materials, not an oracle. If you don’t want to make mistakes like Karolina Opolska, you must always, always, when using materials provided by AI, go to the original sources and check the citations (in Opolska’s book on conspiracy theories, the citations were fabricated). If you don’t use this methodology, you’ll end up in zombie prompting mode with an illusion of competence.

Third, test and verify. Simple as that. AI most often confabulates on specifics: quotes, statistics, dates, names of lesser-known people, publication numbers. You have to check this. However, there is a key to certainty - when the answer contains such elements without a source, treat it as a signal to check. The more certain the matter seems, for example, that someone allegedly sexually abused someone, the greater the emphasis on verification. An effective method: ask for the source or drill down into the details individually. Confabulations fall apart on follow-up, while facts remain consistent. My crudely simple test with “EFF everbridge” was deliberate; I just wanted to see how the AI mode would behave versus a standard SERP. We probably have better cases every day. Do such tests on topics you know. This builds an intuition for where the system can be trusted and where it cannot.

Fourth, remember the confirmation effect from the first part. AI slop is particularly dangerous when it confirms what you already believe. The system is trained to give answers that sound convincing and will be liked, not to tell the truth. The goal of modern algorithms is not TRUTH, i.e., quickly getting to the answer, but ATTENTION and your time spent on a given service. Facebook is probably the best example of this.

Do we still have time for mindfulness?

In the previous article, I wrote about activists who created conspiracy theories based on Google search results. That error stemmed from the human tendency to scan and simplify. Today’s problem is deeper: the system itself generates material for conspiracy theories, and it does so with the authority of an algorithm.

The Stanford researchers end their report with cautious optimism: “if the research community unites around the common goal of making generative search engines more reliable, I think things will get better.” I would like to share this optimism. But observing the direction of the fight between OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and the introduction of commercially unrefined tools… that is, concentration, closed models, the race for engagement instead of truth - I have quite serious doubts. Mindfulness in the age of rapid content consumption is not an easy skill either.

Let’s remember that the philosopher kings who dreamed of setting the semantics, and thus the concept of the noble lie, have to eat; companies have to have an income. And we have to have the knowledge to distinguish myth from fact. The thing is, no one will provide us with this knowledge through the magic of prompting… you still have to acquire it yourself before you ask the machine. Or maybe we should ask directly whether we still want mindfulness and criticality, or whether the world of appearances is more attractive to us?

To be fair: I collected the materials for the upcoming article about Everbridge and their systems with the help of research AI, which I then verified. I did the SERP test with “EFF everbridge” out of curiosity to see how the AI mode behaves.

Noteworthy Sources

Epistemic Injustice in Generative AI

STANFORD UNIVERSITY: Liu, N.F., Zhang, T., & Liang, P. (2023) Evaluating Verifiability in Generative Search Engines | GitHub

It doesn’t matter to me that the text is from 2 years ago; as you can see, the theses are still relevant, and the blame lies with the companies implementing underdeveloped technologies for consumers and businesses.